Oil Prices and Their Economic Impacts | A Perspective by John Darrow

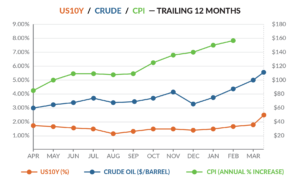

During one of the final Slatt Capital internal weekly calls of 2021, President Michael Kaplan asked each producer for their idea of where the US10Y would finish out the year. While I was not the winner with my pick, my answer was largely predicated on watching the price of oil. At the time, a significant number of traders in the futures market were taking positions that we would go over $100/barrel, and even that we would go above $200/barrel. This was in early December, when Omicron was surging through the country.

Fresh on the heels of the first FED rate hike since 2018 and news this week from Jerome Powell to expect steeper increases in the coming months, I wanted to explore why this time could be different than the last rate hiking cycle from 2015–2018.

In a WSJ article of March 11, Senate Democrats were proposing a “windfall-profits” tax affecting big oil companies that produce or import more than 300,000 barrels per day. Outside of just how punitive this would be on a single industry, and even how unlikely it would be for a bill like this to pass a divided Congress, this reinforces how upside-down our thinking has become with regard to fossil fuels. If you were to look at the 20 most valuable fortune 500 companies from 1995–2020, Exxon was in the rankings in all but 2020. They held number 1 for seven straight years, and were ranked in the top 5 largest companies in 20 of those 25 years. Not surprisingly, four of the five years Exxon wasn’t in the top 5 were the last four years (2017–2020), and 1999 (when it ranked number 8). We could debate the reasons for the drop from 2017–2020, but one thing is clear: money was flowing out of big oil and fossil fuels. I doubt Ms. Warren or anyone cheering for a “wind-fall” profits tax knows that in four of the last 10 years, oil companies actually lost money ($76B in 2020 alone.) Since 2008, big oil has been losing its luster with investors, big banks, and Wall Street. April 2020 was arguably the wake-up call, when front month WTI crude contracts dropped to negative $37/barrel.

As I write this article, Brent finished at $121/barrel and WTI at $114/barrel. The only two other times in the last 40 years—inflation at a 40-year high—that oil has briefly sustained $120/barrel levels preceded serious demand destruction (recessions). Those times were May 1980 and June 2008.

A few facts are worthy of stating:

- If everyone on the planet scrapped their gas automobiles tomorrow and started driving electric vehicles, our global consumption of fossil fuels would drop by only 25%.

- Russia is not a member of OPEC and was not aligned with the interests of OPEC until post 2020.

- The only countries currently in OPEC with the ability to pump more oil are Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

- OPEC is already producing 1MM barrels a day less than their current target, despite consistently increasing their targets.

- The United States is the number one producer of oil and is sitting on the world’s largest reserve.

- Outside of powering our cars or heating our homes, oil is a key component in over 6,000 products we use or consume daily, including anything made with plastics, acrylic, polyester, nylon and spandex, aspirin, antihistamines, soap, perfume, hair dye, cosmetics, hand lotion, toothpaste, shaving cream, deodorant, eyeglasses and contact lenses, golf balls, surf boards, aluminum, bricks, roofing materials, insulation, linoleum, rugs, paint and chewing gum, to name just a few. How many of those do you plan on buying in the next week, month or year?

(For any history buff out there, Daniel Yergin’s The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power is an interesting read.)

So where does that leave us as real estate investors and bankers? I am already advising clients to not chase deals. Rates are still low and there is a lot of liquidity in the market, so now isn’t the worst time to lock in something for 5–10 years. Finally, now isn’t a bad time to think about prepaying that yield maintenance or defeasance loan with 2–3 years left on the term. In a vacuum, yes, the penalties are tough, but there are other reasons I would consider as well (I am currently doing it on one of my CMBS loans).

In the words of Winston Churchill, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

John Darrow

Principal

D: 949.335.7821

john.darrow@slatt.com